A Little Forest Floor in a Raised Bed

Table of contents

New York is home to over 550 community gardens, each with their own unique history, land, and culture. Some focus on food production, some host art and theatrical events, some serve as a hub for the neighborhood, and still others create ecologically resilient wildlife habitat. In one sense, these are all different aspects of the same goal: stewarding a healthy ecosystem for the local multi-species community.

Communities are shaped by their particular environment. During the New York financial crisis of the 1970s, property owners in the Lower East Side burned down and abandoned their apartment buildings, leaving behind a pile of rubble and not much else. Local residents cleaned up the lot, shovel by shovel, and created spaces to grow food and for their children to play. Other community gardens were started by an organization such as the New York Restoration Project, which cleaned up an illegal dumping ground along Harlem River to create Swindler Cove. Swindler Cove now contains restored wetlands, native plantings, and a children’s garden.

Our work as community gardeners is informed by both the history of the land and the history of the people in the neighborhood. And as both are apt to change over time, we must be flexible and adapt to a changing environment.

Twenty years ago, Green Oasis Community Garden received ample sunlight, and the raised beds were replete with tomatoes, basil, and strawberries. At the same time, the trees that were planted when the garden was founded in 1981 were starting to mature and grow larger. These days, Green Oasis has a high level of canopy coverage casting shade throughout the garden, making it impractical to grow fruits and vegetables.

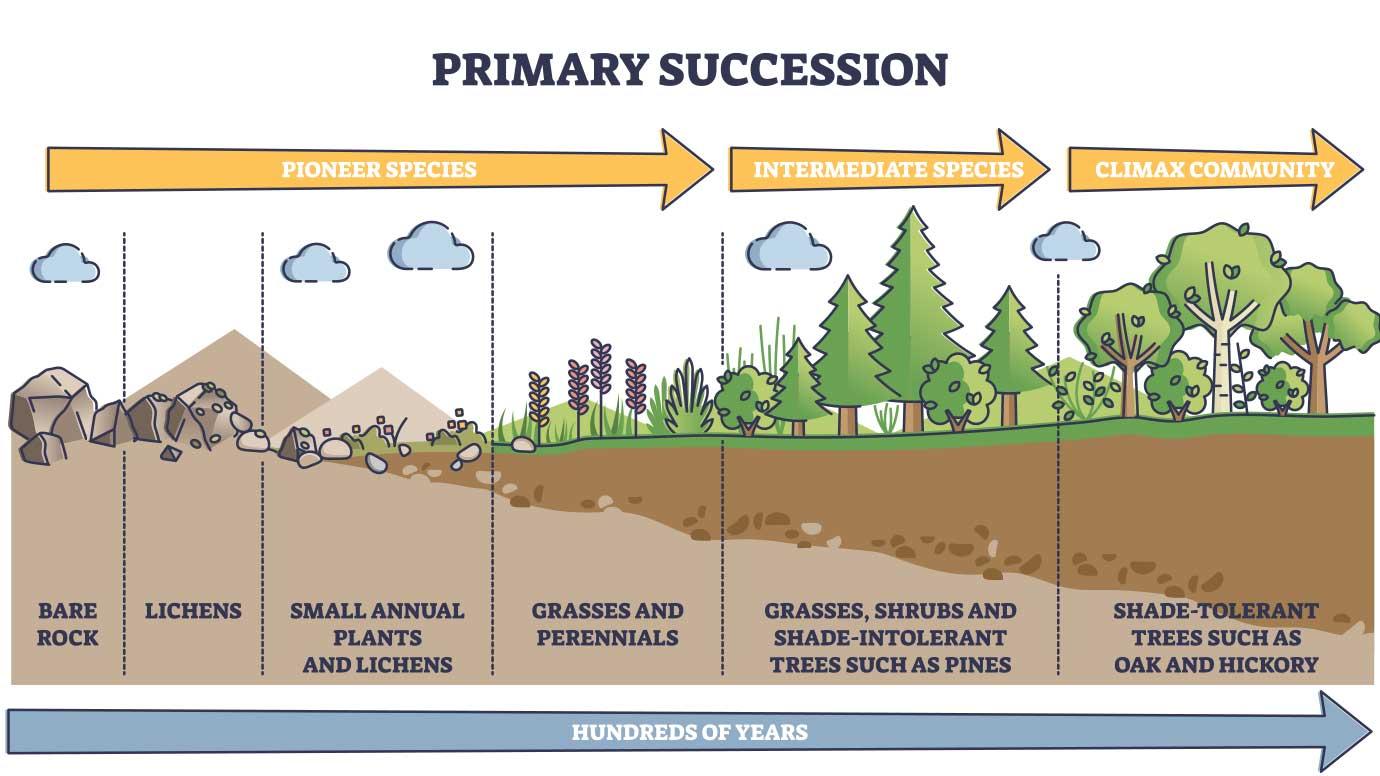

The changes at Green Oasis resemble the natural process of ecological succession. In the Eastern Temperate Forests ecoregion of North America, land left to its own devices will be first occupied by grasses, herbs, and shrubs. At this point, shade-intolerant evergreens such as eastern white pine start to grow larger and shade out the previously growing herbs, and at the same time, create habitat for shade-tolerant plants such as Pennsylvania sedge. Finally, shade-tolerant hardwoods such as white oak and shagbark hickory grow and shade out the pine trees. Perhaps later, a wildfire or human activity will reset the cycle back to the beginning.

University of Chicago newsroom

University of Chicago newsroom

Ecological communities, like human communities, are always changing and adapting to the changing environment. It is true that humans have the ability to change the local environment, and do so in an ecologically sound manner. For example, in The Mushroom at the End of the World, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing describes how matsutake (lit. pine mushroom) farmers in Japan use the ancient coppicing technique to indefinitely maintain a pine forest where matsutakes grow well. At the same time, we must acknowledge that each kind of environment has its own advantages and provides habitat to different kinds of flora and fauna (including humans).

While a forest ecosystem is not suited to growing traditional community gardening crops, they are perfect for growing mushrooms, leafy greens, and pawpaws. And remember that food production is only one aspect of a community garden. A shady garden reduces the urban heat island effect, providing humans a (free) respite from increasing temperatures. A dense forest of trees filters air pollution and reduces flooding by absorbing stormwater. Of course, a forest ecosystem is home to countless kinds of ferns, sedges, spring ephemerals, asters & goldenrods, insects, birds and mammals.

As community gardeners, our first instinct may be to prune large tree branches and bring more sunlight to our raised beds. But an alternate path exists. What if we embraced the natural process of ecological succession, accepting change and the passage of time? We can fondly remember the times when we could readily grow vegetables and fruits, and also look towards the exciting opportunities now available to us in a forest ecosystem. And there are always other gardens that are suitable for larger-scale food production: for example, McCarren Demo Garden in Brooklyn, which donates their produce to local community fridges.

In an ecosystem, the environment (climate, precipitation, sunlight, soil type) shapes the interactions between the fauna and the flora. Part of being a member of an ecological community is learning to work with the environment rather than against it. If we reduce our dependence on constant prunings, regular watering, laborious weeding, and expensive fertilizers, we can create a more reliable, sustainable, and resilient garden.

Raised beds at Green Oasis

Green Oasis is a large community garden, almost half an acre. Most of the garden’s plantable areas are communally stewarded grounds full of grasses, herbs, shrubs, and trees. In addition, we have around 20 raised beds. Most are allocated to individual garden members; one is used as a community medicinal herb garden. Some garden members grow shade-tolerant produce such as kale, chili peppers, and shiso, while others grow an assortment of wildflowers.

Raised beds can be thought of as a opportunity for gardeners to exhibit an artistic design suited to their unique sense of aesthetics. One gardener’s raised bed is a microcosm of the ecosystem at Marine Park in Brooklyn, containing the plants local to that area, as well as found objects such as broken tiles and lamps. Another gardener plants her favorite ornamental flowers and includes bee baths made out of a branch and artfully arranged bottlecaps.

Soft landings

As a woodland garden, Green Oasis is home to many trees, both native and introduced. Native trees specifically are hosts to an incredible variety of insects, many of which are adapted specifically to only eat the leaves of one type of tree. After feeding on the tree foliage, caterpillars travel to the leaf litter below the host tree in order to pupate and overwinter. If those trees are underplanted with mowed turfgrass, caterpillars will lack the habitat to complete their lifecycle. As described by Heather Holm, soft landings are safe, undisturbed plantings of native grasses, ferns, and forbs under host trees. Soft landings provide food and shelter, allowing butterflies, moths, and many other insects to pupate and survive the winter.

At Green Oasis, we have two large littleleaf linden (American basswood) trees, which are hosts to over 150 species of caterpillars. Currently, these lindens are on beds of vinca, an invasive vine. We have the opportunity to do much better. We wanted to create a beautiful, resilient, and low-maintenance forest floor that would allow our butterflies and moths to thrive in every stage of their lifecycle.

However, as beginner gardeners, we weren’t sure what kinds of native plants would work best in our garden. While online resources list the preferred light exposure and moisture requirements for each plant, growth patterns depend greatly on the specific location. What sedges grow best in dappled morning light? Can a large fern be underplanted with Pennsylvania sedge? What selection of flowers will ensure continuous blooms throughout the year in our particular climate? To answer these questions, we decided to make an experiment: a little forest floor in a raised bed. It’s important to remember that a raised bed is not the same as the the ground in the garden; in particular, the soil is completely different. Still, we believe this exercise will be useful, and the bed will be ecologically beneficial in its own right.

A little forest floor

Our goal for our raised bed was to create a planting that is reminiscent of a typical New York mature forest floor. We were interested in creating visual interest through texture and varying heights, rather than focusing on flowers and color (as is typical of the English gardening tradition). Our design emphasizes sedges and grasses, which are sometimes considered “uninteresting” or “filler” plants. Instead of choosing “the most beautiful” plants at the nursery, we started with the axiom that all plants are inherently beautiful, and asked ourselves how we could understand each plant’s individual beauty and how to create an composition that remains ecologically and aesthetically beautiful throughout the year.

Mt. Cuba Center

Mt. Cuba Center

While flowers do provide pollen and nectar, insects also need habitat. Sedges and grasses create dense mats where pollinators and other insects can shelter and over-winter, while also protecting against the introduction invasive species. They are also crucial in reducing soil erosion and absorbing stormwater.

In a previous blogpost, we wrote about the design process for our first native plant garden, which was largely inspired by reading Planting in a Post-Wild World by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West. It focuses on the idea of designed plant communities and a relational approach to garden design, which we’ll refer to below. Briefly, we focus on how the different plants relate to each other, both aesthetically and ecologically. For example, the idea of planting a soft landing under a native tree, or surrounding tall flowers with a diversity of groundcover plants.

Plant selection

We used the New York City Native Planting Guide to understand the different kinds of upland forest ecosystems in New York (such as mixed oak-hickory forest and rich mesophytic forest), and the plants that are typical to those ecosystems. It also offers excellent guidance on planting in altered urban lots such as most community gardens.

From the catalogs at our local native plant nurseries, we filtered for the shade-tolerant and dry-to-medium moisture, drought-tolerant offerings in order to decide what to plant.

Structural layer

The structural layer consists of long-lived plants providing year-long structure and clarity of form. We chose bottlebrush grass (Elymus hystrix), slender woodoats (Chasmanthium laxum), eastern woodland sedge (Carex blanda), and interrupted fern (Osmunda claytonia).

Bottlebrush grass is a cool-season grass (meaning that it grows actively in the spring and fall), features spectacular seedheads and is the host for the northern pearly eye butterfly.

mowildflowers.net

mowildflowers.net

Illinois Department of Natural Resources

Illinois Department of Natural Resources

Slender woodoats is a warm-season grass, growing actively in the summer, and features staccato, delicate seedheads, and is the host for various skipper butterflies. Both grasses’ seeds are an important food source for birds.

Gowanus Canal Conservancy

Gowanus Canal Conservancy

Gary L. Spicer

Gary L. Spicer

Eastern woodland sedge is a large, clumping evergreen sedge, resilient to a wide variety of environmental conditions.

Mt. Cuba Center

Mt. Cuba Center

Finally, interrupted fern is a large fern with prominent fiddleheads and a unique texture.

James St. John

James St. John

Seasonal theme layer

While flowers were not the main visual focus of our design, they are still important aesthetically as well as for pollinators. We were interested in flowers that are not usually considered “ornamental,” but provided outsized benefit to insects. We chose spiderwort (Tradescantia virginiana), slender mountainmint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium), late figwort (Scrophularia marilandica), and white wood aster (Eurybia divaricata), a selection that ensures blooms throughout the year.

Spiderwort produces purple flowers in spring. They only bloom for one day, but the plant has so many buds the blooms are continuous. They provide abundant nectar for butterflies and hummingbirds, as well as pollen for bumblebees, little carpenter bees, and sweat bees. The leaves of spiderwort are remarkably grass-like, adding to the overall visual effect of the planting.

theplantnative.com

theplantnative.com

Slender mountainmint produces small but showy white flowers in the summer and is a veritable magnet for bees and butterflies. It features a strong mint aroma.

nativeplantsasheville.com

nativeplantsasheville.com

Late figwort produces small red cup-shaped flowers in the summer that are full of nectar for leaf-cutter bees, sweat bees, bumblebees, butterflies, and ruby-throated hummingbirds.

NC State Extension

NC State Extension

Finally, white wood aster produces white daisy-like flowers in the fall, providing pollen and nectar to insects at a time when little food is otherwise available. The seedheads are also an important food source for birds through the winter.

In a deciduous forest, the summer is characterized by intense shade, making it so few flowers can grow. Therefore, plants that bloom in the early spring (we will discuss spring ephemerals below) and fall, such as asters and goldenrods, are critical components of the ecosystem. Forest insects have co-evolved with the flowers and wake up from hibernation at the same time their preferred flowers are in bloom.

Wild Seed Project

Wild Seed Project

Groundcover layer

The groundcover layer consists of competitive and clonal-spreading plants that provide soil fertility and structure, erosion control, stormwater capture, invasive species suppression, biodiversity, pollutant uptake, moisture retention, and wildlife habitat. We chose a variety of sedges and ferns for this layer: field oval sedge (Carex molesta), long-beaked sedge (Carex sprengelii), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), low woodland sedge (Carex socialis), eastern narrow-leaved sedge (Carex amphibola), rosy sedge (Carex rosea), Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), and broad beech fern (Phegopteris hexagonoptera). The large number of species is to maximize the biodiversity, but also act as an experiment to see which ones do well and which do poorly. Below, broad beech fern and Pennsylvania sedge are pictured.

Katja Schulz

Katja Schulz

Mt. Cuba Center

Mt. Cuba Center

Dynamic filler layer

The dynamic filler layer consists of short-lived but fast-growing and readily self-seeding plants that fill in gaps left by disturbances or plant deaths before invasive species take over. We chose Jacob’s ladder (Polemonium reptans), which has blue flowers in spring that are a favorite of many native bee species.

Ryan Kaldari

Ryan Kaldari

Spring ephemeral layer

In forests, spring ephemerals flowers bloom before trees leaf out in the spring and then die back completely when summer starts and the garden becomes shady, reappearing the next year. They are critical food sources for many kinds of insects, and are unfortunately in danger due to the proliferation of invasive species in New York. For this layer, we chose bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), trout lily (Erythronium americanum), Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria), spring beauty (Claytonia virginica), and mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum). Below, Dutchman’s breeches and mayapple are pictured.

NYC Parks

NYC Parks

Jay Sturner

Jay Sturner

Bloodroot is a pollen source for early-season native insects such as sweat bees, cuckoo bees, small carpenter bees, bee flies, mining bees, and beetles. It is used as a red natural dye by Native American artists.

NYC Parks

NYC Parks

ithacawaldorf.blogspot.com

ithacawaldorf.blogspot.com

On plant selection

Although we tried to choose plants with properties suitable for the different layers as described by Rainer and West, plants do not fit so neatly into human-created categories. We were not always able to find a plant that satisfied all of the properties, both because of the small selection available to non-professional gardeners, and also because plants exist on a spectrum in terms of longevity, aggressiveness, structure, and so on, all of which are impacted by the particular local conditions.

For example, some native plants are labeled as “aggressive.” This can be good in the sense that they form a groundcover that suppress invasive species, or bad because they outcompete all the other native plants in the area. It is hard to know a priori what will be too aggressive (or perhaps not aggressive enough). Similarly, online resources disagree on whether interrupted fern is long-lived, making it unclear whether we should use it in the structural layer. In the end, the particular site conditions have an enormous influence and it is impossible to predict the exact behavior of plants beforehand. We expect that not everything will go according to plan and we will need to make changes in the future.

Plant layout

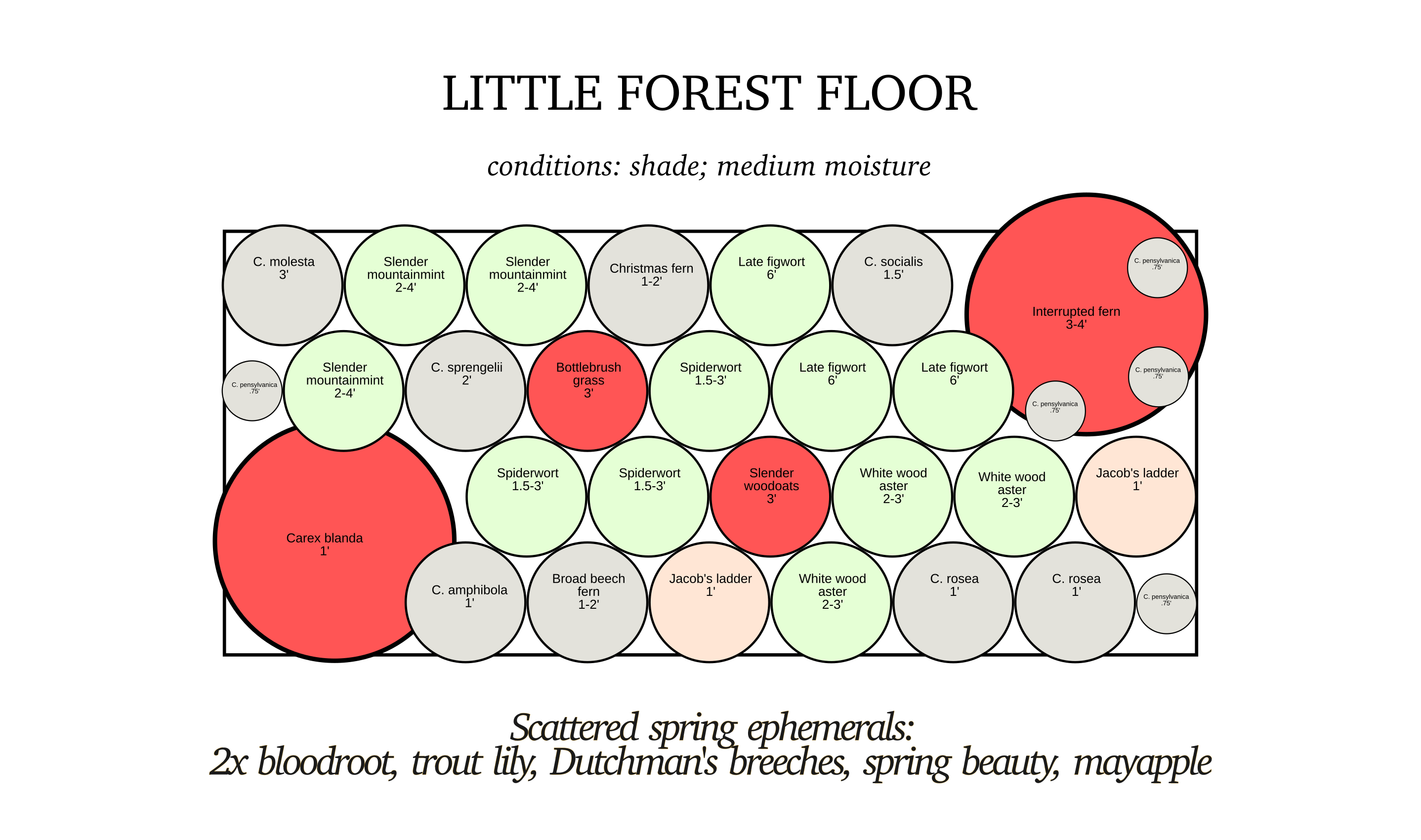

The raised bed is 8 feet by 3.5 feet, for a total of 28 square feet. We planted in staggered rows to maximize the planting space (and minimize bare soil), as shown below. This diagram uses the diameter of the circle to represent a plant’s projected maximum breadth, which is useful when planning out the layout. Most are given a 1’ diameter circle. Approximate expected heights are listed as well. Pennsylvania sedge underplants the large interrupted fern as well as in tight spots.

The structural plants are placed first at prominent locations. Drifts of seasonal theme plants are interspersed throughout, then groundcover and dynamic filler plants are used to fill in all the gaps. Because they don’t directly compete with other plants, spring ephemerals are scattered throughout (we planted 2 of each). We tended to place taller plants on the north side so as not to shade out shorter plants, but as all the plants are shade-tolerant anyway, this was not a primary consideration.

Plant acquisition

We acquired plants from the city-run PECAN nursery, the North Brooklyn Parks Alliance native plant giveaway, Plant Buying Collective, Lowlands Nursery, and the Kingsland Wildflowers nursery.

In general, forest ecosystem natives are hard to come by even at native plant nurseries, especially for hard-to-grow species like sedges, ferns, and spring ephemerals. We were grateful to find nurseries that recognized the important ecological value of these plants.

The NYC Parks Plant Ecology Center and Nursery (PECAN) in Staten Island has a wide selection of native plants, including various sedges and ferns. They only work with city-affiliated organizations, and the plants they grow for ecological restoration projects are also suitable for community gardens. PECAN ethically sources all of their seed from within 100 miles of New York. Even within a particular species of plant, genetic material varies considerably, and plants that are sourced locally are most well adapted to local insects. In general, it is extremely difficult to find nurseries that even mention the ecotype of their offerings, so PECAN is an invaluable resource in this regard. Additionally, PECAN is quite affordable, selling most plugs for $2.50, whereas other nurseries might charge up to $10.

Ordering from PECAN is not straightforward; there is no readily accessible online catalog. First, email the address on the PECAN website, and they will send back an order intake form where you can input your project details. They will send you a spreadsheet with the current inventory and you can make selections from there. Be quick, because inventory changes rapidly. Finally, you can arrange a pickup time at the nursery. PECAN does not deliver, and it is inconvenient to get to the nursery by public transit. We took the ferry from Battery Park to Staten Island, and then the S62 bus to Victory Blvd/Baron Blvd. We are planning to place a much larger order next year, and will likely rent a car or truck for transport.

This year, the North Brooklyn Parks Alliance ran a native plant giveaway at Under the K Bridge Park in September and October, giving away over 10,000 plants for free (we found out on the NYC Pollinator Working Group mailing list). Their selection was excellent, covering a wide range of site conditions and including grasses and rarer plants such as late figwort. The nursery operator was incredibly kind and helpful when we visited. If they repeat the giveaway next year, be sure to check it out.

We purchased spring ephemerals online from Plant Buying Collective. We placed the order in September and the plants were delivered in November as bare roots, rhizomes, or corms. We were unable to find a local source for spring ephemerals, but purchasing from Plant Buying Collective was straightforward and affordable.

We also got a few plants at Lowlands Nursery in Gowanus as well as the nursery at Kingsland Wildflowers in Greenpoint. Both have excellent volunteer programs for those who are interested in learning some nursery skills.

Site preparation

This raised bed didn’t need much preparation. The soil level was topped off with soil from a local garden store. Before planting, we briefly watered the soil so it could settle a bit.

Site installation

Installation, like layout, occurs by layer. We first planted the structural layer, then the seasonal theme layer, filled in any gaps with the groundcover and dynamic filler layers, and finally, interspersed the spring ephemerals. The placement of the structural layer is most critical; after that, it is better to place the other plants more freely, using the layout as an approximate guide rather than an exact specification. We planted in late September. Fall planting is ideal for native plants because it reduces the need for watering and allows the plants to settle in over the winter before starting to grow next spring.

Post-installation

We watered the plants thoroughly after the inital installation, and then kept watering for a few weeks. The weather got cold quite quickly, so we have paused watering until the spring. We expect to need to water occasionally for the first year or so, and then the plants should be mature enough to not need watering unless in extreme drought conditions. One issue we had was the disappearance of a white wood aster, presumably due to a squirrel or rat. We have found that they often like to dig up newly planted young plants, though they don’t usually eat them or carry them away. In the future, it could make sense to encircle young plants with hardware cloth for a few weeks while they get established.

A sign of the times

One of my favorite parts of living in New York is getting to visit other community gardens and learning from their efforts. Hand painted signs are a common sight, identifying different areas of the garden, the plantings in raised beds, instructions for composting, and more. These signs are important as a marker of human activity and creative expression.

For our raised bed, we made a sign by sanding and oiling a piece of scrap wood, then painting with a brush and calligraphy ink. Beneath the sign is an NFC tag that links to this blog post. We hope that visitors appreciate the ecological and artistic intent of our little forest floor in a raised bed.